Difference between revisions of "Speech Technologies"

(a correction) |

(a correction) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

The speech technologies deals with voice, which is the dominant tool of interpersonal communication.<ref>LALWANI, Mona. Personal assistants are ushering in the age of AI at home. Engadget [online]. 2016, Oct 5. Available online at: https://www.engadget.com/2016/10/05/personal-assistants-google-home-ai/ (Retrieved 5th January, 2017).</ref> The importance of the voice was acknowledged also by the fact that 16th April was chosen as World Voice Day.<ref>SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH, Judy. Voice of the people. The Jerusalem Post [online]. 2015, Apr 26. Available online at: http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Health/Voice-of-the-people-399185 (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).</ref> | The speech technologies deals with voice, which is the dominant tool of interpersonal communication.<ref>LALWANI, Mona. Personal assistants are ushering in the age of AI at home. Engadget [online]. 2016, Oct 5. Available online at: https://www.engadget.com/2016/10/05/personal-assistants-google-home-ai/ (Retrieved 5th January, 2017).</ref> The importance of the voice was acknowledged also by the fact that 16th April was chosen as World Voice Day.<ref>SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH, Judy. Voice of the people. The Jerusalem Post [online]. 2015, Apr 26. Available online at: http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Health/Voice-of-the-people-399185 (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).</ref> | ||

| − | == Main | + | == Main Characteristics == |

Speech technologies could be divided between technologies used in medicine and technologies for commercial use. While the former group is represented primarily by [[Electrolarynx|electrolarynges]] and [[Speech prostheses|speech prostheses]], [[Intelligent Personal Assistants|intelligent personal assistants]] belong to the latter category. [[Speech synthesizers|Speech synthesis]] is used for both purposes. It is contained in intelligent personal assistants or GPS navigations, but also in systems for visually impaired and speech synthesizers for people who lost their voice.<ref name="taylor">TAYLOR, Paul. Text-to-Speech Synthes. University of Cambridge Department of Engineering [online]. 2014. Available online at: http://mi.eng.cam.ac.uk/~pat40/ttsbook_draft_2.pdf (Retrieved 2nd February, 2017).</ref> These technologies appear in two forms. It could be devices, software or a combination of both. | Speech technologies could be divided between technologies used in medicine and technologies for commercial use. While the former group is represented primarily by [[Electrolarynx|electrolarynges]] and [[Speech prostheses|speech prostheses]], [[Intelligent Personal Assistants|intelligent personal assistants]] belong to the latter category. [[Speech synthesizers|Speech synthesis]] is used for both purposes. It is contained in intelligent personal assistants or GPS navigations, but also in systems for visually impaired and speech synthesizers for people who lost their voice.<ref name="taylor">TAYLOR, Paul. Text-to-Speech Synthes. University of Cambridge Department of Engineering [online]. 2014. Available online at: http://mi.eng.cam.ac.uk/~pat40/ttsbook_draft_2.pdf (Retrieved 2nd February, 2017).</ref> These technologies appear in two forms. It could be devices, software or a combination of both. | ||

Revision as of 10:05, 12 April 2017

Speech technologies are technologies or devices that can understand and/or produce human-like speech. The speech generation is useful in applications such as text-to-speech, electrolarynges, speech prostheses or intelligent personal assistants. The former three technologies are used as a medical devices for people, who lost their voice. Speech synthesizers are also incorporated into devices which helped visually disabled people. Intelligent Personal Assistants allow the users to use their devices hands-free by merely saying required commands, mostly in plain, natural speech.

The speech technologies deals with voice, which is the dominant tool of interpersonal communication.[1] The importance of the voice was acknowledged also by the fact that 16th April was chosen as World Voice Day.[2]

Contents

Main Characteristics

Speech technologies could be divided between technologies used in medicine and technologies for commercial use. While the former group is represented primarily by electrolarynges and speech prostheses, intelligent personal assistants belong to the latter category. Speech synthesis is used for both purposes. It is contained in intelligent personal assistants or GPS navigations, but also in systems for visually impaired and speech synthesizers for people who lost their voice.[3] These technologies appear in two forms. It could be devices, software or a combination of both.

Historical overview

The first speaking machines were developed in Antiquity and Middle Ages. Nonetheless, they were not genuine speaking machines since they depended on people speaking inside of them. The first genuine speaking machine was introduced by Hungarian civil servant and inventor Wolfgan von Kempelen. He described his speech synthesiser in a book "Mechanismus der menschlichen Sprache nebst der Beschreibung seiner sprechenden Maschin" [The Mechanism of Human Speech, with a Description of a Speaking Machine] published in 1791.[4]

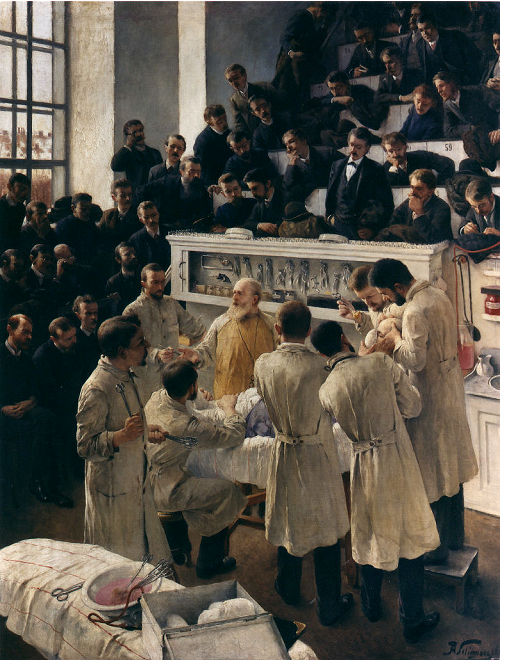

In the 19th century, researchers focused also on the help people, who lost their voice or have serious problem with their throat. Jan Nepomuk Czermak described the first laryngeal prosthesis in 1859. His attempt was followed by the introduction of various speech prosthesis and artificial larynges.[5] Later on, an Austrian surgeon Theodore Billroth performed the successful total extirpation of the larynx.[6]

20th century was an important breakthrough in various fields of speech technologies. The speech synthesis started to be mechanized by the introduction of Voder in 1930.[7] New techniques of voice synthesis also made the synthetic voice sounding more natural and lately allow to preserve the voices of patients, who are losing their voice.[8] The first electrolarynges were introduced in 1942 by Wright.[5] Surprisingly, the first tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis was not developed by a professional, but it was conducted by a patient using a red hot ice pick in 1931. The surgeons were, however, unable to replicate this procedure.[9] Therefore, it was abandoned until Erwin Mozolewski presented his tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis.[10]

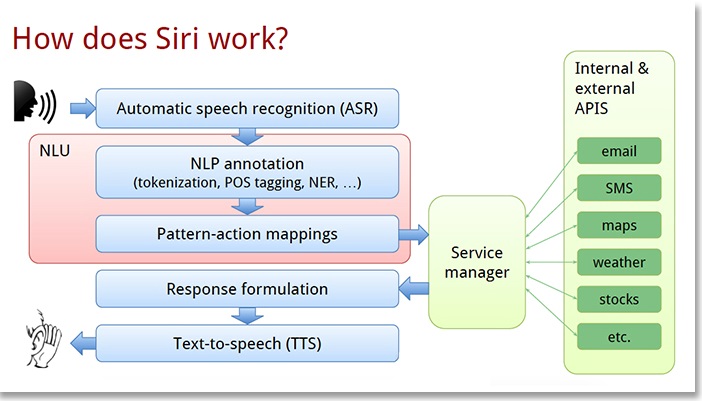

In the middle of 20th century, the first speech recognition system were introduced. The first system was "Audrey" which was able to recognised digits spoken by a single voice. It was followed by IBM's "Shoebox" presented at 1962 World's Fair. It was able to recognised 16 English words. Another important system for voice recognition was "Harpy", which was developed by U.S. Department of Defense between years 1971 and 1976. It could recognise 1011 words similarly as 3 years old child.[11] Apple presented the idea of intelligent personal assistant in 1987. It was entitled "Knowledge Navigator", but the advertised product have never been developed.[12] The first publicly available personal assistant was Siri introduced by Apple in 2010.[13] It was followed by the similar products of other companies as Alexa, Google Now, and Cortana.[14] Siri was a software, which was contained in iPhones. In 2014, Amazon.com presented first intelligent personal assistants' device Amazon Echo, which contains Alexa.[15] Its introduction also provoke the introduction of similar devices as Google Home, Apple HomeKit, Lenovo Smart Assistant, etc.[14]

Important Dates

- 1769 - Wolfgang von Kempelen developed the first genuine speech synthesizer[16]

- 1859 - the first pneumatic laryngeal prosthesis was introduced by Jan Nepomuk Czermak[5]

- 1873 - Billroth conducted the first successful total laryngectomy[5]

- 1931 - the first laryngeal puncture was conducted by a patient[17]

- 1937 - the speech synthesizer Voder was unveiled[7]

- 1942 - Wright developed the first electrolarynx "Sonovox"[18]

- 1952 - Bell Laboratories presented "Audrey"[11]

- 1972 - Erwin Mozolewski introduced a tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis[19]

- 1976 - "Harpy" was developed[11]

- 1987 - Apple Knowledge Navigator was presented[20]

- 4th February 2010 - Siri Inc. unveiled Siri[13]

- 6th November 2014 - Amazon.com, Inc introduced Amazon Echo[15]

Enhancement/Therapy/Treatment

Therapy & Treatment

The purpose of speech prostheses and electrolarynges is to return the ability to speak to patients who underwent total laryngectomy or lost their voice by any other way.[21] Certain speech synthesizers could be also used for this purpose, even though speech synthesis is used also in non-therapeutical applications.[3] Patients could also achieve oesophageal speech, but it is difficult to learn and certain patients are not able to communicate this way.[22] Each technique of voice restoration has its pros and cons. Electrolarynx's speech sound mechanical and depends on the mechanical device, but it is easy to achieve and it is used, when any other methods fails.[21] Speech prosthesis has to be installed during surgery, the prosthesis has to be removed periodically[23] and the pitch is considerably low for women,[24] but in comparison to electrolarynx it has a certain pitch control and better ineligibility.[23] Speech synthesis could preserve patient's voice, but it depends on the voice conservation, which could be challenging.[8]

Customers' review suggest that intelligent personal assistants could be helpful for elderly and disabled. The devices could make them more independent due to control of environment which they provide.[25] Customers also claim that the devices could call the help when elderly or disabled person have an accident.[26] Notwithstanding, this claim has not been supported by a research, yet.

Speech synthesis is used in various applications and devices for the blind or vision impaired people. It enables them to read the content from the screen.[8] The speaking devices as toys or GPS also benefit from speech synthesis. It is also used in call centres where, it could handle with common tasks of customers.[3]

Enhancement

Intelligent personal assistants (IPA) are meant to help their user deal with several tasks, organise information and provide help with complex tasks. Siri, the first IPA, was originally develop to solve military tasks[27]. However, IPA are used in a medical care,[28] business, transportation[29] or shopping[30] at present. IPA could also control the smart devices which are in the household of their user, even though certain brans support just certain IPA.[31] IPA or speech synthesizers could help their users with the acquisition of foreign language.[32][33][34]

Ethical & Health Issues

Efficiency

The issue, with which every speech technology struggles, is efficiency and quality of their performance. As was mentioned in a previous section, the quality of the voice produced by elecrolarynx is low, even though, a newly introduced electrolarynges contain pitch control.[18] Although, the voice produced by voice prosthesis and speech synthesizers sounds better, it is still not natural.[3][24][35] Finally, intelligent personal assistants struggle with the recognition of different accents,[36] are only as efficient as many application they cooperate and run only on their home device at the moment.[37]

Privacy issues

The main issue linked with IPA is data collection. IPA collect various data about their users as personal contacts, location, and preferences etc. in order to provide adequate service. Moreover, their speech synthesis is not processed at the device but in the remote centre.[38] Those data are valuable for companies, which collected them and could be used for their commercial purposes.[39] The data could be also misused, if they are stolen by a third party.[40] Majority of IPA listen all the communication which happen around them. Although, they could be switched off, this feature is not always used since it is inconvenient.[41] The issue applies to some extend also on speech synthesizers, especially on apps, which provide speech synthesis.[42]

Naturalness

The problem of uncanny valley could be also applied on speech technologies. Jan Romportl claims that the effect of uncanny valley might cause that the more natural-sounding voice, which is produced by the current speech synthesizers, might not been entirely accepted.[43] In addition, Gatebox IPA rose a controversy and was deemed to be creepy by certain journalists due to the fact that it tends to be considerably personal.[44] Nicholas Brazzi also warns that personal connection to IPA could have negative effect on decision making and could be potentially dangerous and life threatening.[45]

Post-surgery state

The use of certain types of electrolarynges and speech synthesizers could be limited after surgery due to the post-surgery state of the patient. Patient could be weak[46] and the tissue in his or her neck could be harmed by surgery or radiation. While certain conditions could change in a few days after surgery, if the tissue is scarred or radiated, the patient could not use a neck-type electrolarynx.[47]

Infection

The intra-oral elecrolarynges tend to be corrupted by infection and therefore, patients have to care about them carefully.[48] The appropriate hygiene is also necessary in the handling with speech prostheses.[49]

Public & Media Impact and Presentation

Speech technologies feature in several sci-fi films, series, books and video games. One of the best known is HALL from Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. It is a computer which turned to endanger a staff of the spaceship, where it is installed. When it is switched off he sang Daisy Bell. Arthur C. Clark, the author of the plot, was inspired by his experience with the real computer, which was able to sing this song.[50]

Several speech technologies, which are already available also appear on screen. Electrolarynx was used by characters in Mad Max[51], South Park[52] or My name is Earl[53]. Siri, IPA developed by Apple, appeared in The Big Bang Theory[54], where one of the main characters falls in love with her, and was parodied in The Simpsons[55].

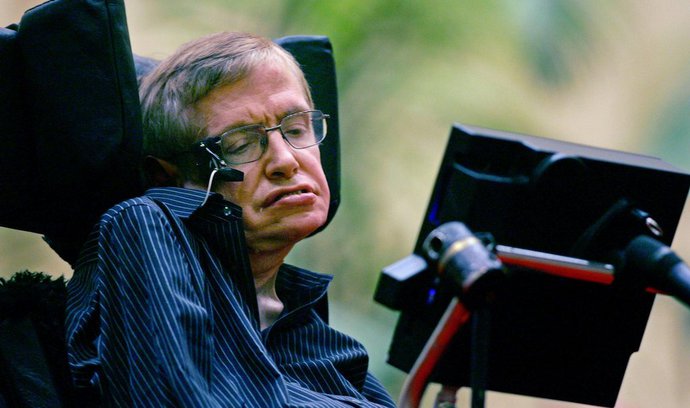

The most renowned user of speech synthesis might be Stephen Hawking, British physicist and cosmologist. Hawking lost his voice due to tracheotomy which he underwent in 1985. He uses a system which Intel developed for him.[56] Intel released this software, which is entitled ACAT, for free. It is meant to helped patients with the same diagnosis as Hawking has, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and other disabled people.[57]

The loss of voice is caused by total laryngectomy due to a cancer in many cases. The main factor causing this type of cancer is smoking. Therefore, people who use electrolarynx or speech prostheses are involved in several anti-smoking campaigns, e.g. a cowboy singing with his electrolarynx a song with a refrain 'You don't always die from tobacco'[58] or a man with electrolarynx, who sold cigarettes and told a story of his life.[59]

Public Policy

The devices which collect personal data have to comply certain regulations.[60] In addition, their use is banned in some companies, e.g. IBM.[61]

Related Technologies, Projects or Scientific Research

IBM works on the enrichment of speech synthesis by emotions.[62]

Several devices which are listed among Internet of Things (IoT) devices could be controlled by IPA.[31]

References

- ↑ LALWANI, Mona. Personal assistants are ushering in the age of AI at home. Engadget [online]. 2016, Oct 5. Available online at: https://www.engadget.com/2016/10/05/personal-assistants-google-home-ai/ (Retrieved 5th January, 2017).

- ↑ SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH, Judy. Voice of the people. The Jerusalem Post [online]. 2015, Apr 26. Available online at: http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Health/Voice-of-the-people-399185 (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 TAYLOR, Paul. Text-to-Speech Synthes. University of Cambridge Department of Engineering [online]. 2014. Available online at: http://mi.eng.cam.ac.uk/~pat40/ttsbook_draft_2.pdf (Retrieved 2nd February, 2017).

- ↑ DUDLEY, Homer, TARNOCZY, T. H. The speaking machine of Wolfgang von Kempelen. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 22, 151-166. Doi:10.1121/1.1906583. Available online at: http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:2316415:3/component/escidoc:2316414/Dudley_1950_Speaking_machine.pdf (Retrieved 2nd February, 2017).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 KEITH, Robert L., SHANKS, James, Laryngectomee Rehabilitation: Past and Present. In: Speech and Language: Advances in Basic research and Practice. New York: Academic Press, 1983. Available online at: https://books.google.cz/books?id=0C60BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA126&lpg=PA126&dq=Cooper-Rand+electrolarynx&source=bl&ots=or27eudDf2&sig=22heagC08Fpk57qGILvufHxwCyM&hl=cs&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi1--bt3r7RAhWGuxQKHbrFCC04ChDoAQgdMAE#v=onepage&q=Cooper-Rand%20electrolarynx&f=false (Retrieved 13th January, 2017).

- ↑ KAZI, R. A., et al. Christian Albert Theodor Billroth: Master of surgery. Journal of postgraduate medicine, 2004, 50.1: 82. Available online at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/2074/1/jp04025.pdf (Retrieved 25th February, 2016).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 DUNCAN. Klatt’s Last Tapes: A History of Speech Synthesisers. Communication Aids [online]. 2013, Aug 10. Available online at: http://communicationaids.info/history-speech-synthesisers (Retrieved 2nd February, 2017).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 JŮZOVÁ, M., TIHELKA, D., MATOUŠEK, J. Designing High-Coverage Multi-level Text Corpus for Non-professional-voice Conservation. In: Speech and Computer. Volume 9811 of the series Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer, 2016, pp 207-215. Doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-43958-7_24 Available online at: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-43958-7_24 (Retrieved 16th February, 2017).

- ↑ BLOM, Eric D. Current Status of Voice Restoration Following Total Laryngectomy. Oncology [online]. 2000, Jun 1. Available online at: http://www.cancernetwork.com/head-neck-cancer/current-status-voice-restoration-following-total-laryngectomy (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ MOZOLEWSKI, Erwin S., et al. "Arytenoid vocal shunt in laryngectomized patients." The Laryngoscope 85.5 (1975): 853-861.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 PINOLA, Melanie. Speech Recognition Through the Decades: How We Ended Up With Siri. PCWorld [online]. 2011, Nov 2. Available online at: http://www.pcworld.com/article/243060/speech_recognition_through_the_decades_how_we_ended_up_with_siri.html (Retrieved 28th February, 2017).

- ↑ DUBBERLY, Hugh. The Making of Knowledge Navigator. DDO [online]. 2007, Mar 30. Available online at: http://www.dubberly.com/articles/the-making-of-knowledge-navigator.html (Retrieved 5th January, 2017).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 HARRISON, Natalie and BREWER, Teresa. Apple Launches iPhone 4S, iOS 5 & iCloud. Apple [online]. 2011. Oct 4. Available online at: http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2011/10/04Apple-Launches-iPhone-4S-iOS-5-iCloud.html (Retrieved 16th December, 2016).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 POGUE, David. The Problem with Tech Copycats. Scientific American [online].315(5), p. 23-23. Available online at: http://ve5kj6kj8s.scholar.serialssolutions.com/?sid=google&auinit=D&aulast=Pogue&atitle=The+Problem+with+Tech+Copycats&id=doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1116-23&title=Scientific+American&volume=315&issue=5&date=2016&spage=23&issn=0036-8733 (Retrieved 19th December, 2016).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 WELCH, Chris. Amazon just surprised everyone with a crazy speaker that talks to you. The Verge [online]. 2014, Nov 6. Available online at: http://www.theverge.com/2014/11/6/7167793/amazon-echo-speaker-announced (Retrieved 20th December, 2016).

- ↑ WOODFORD, Chris. Speech synthesizers. EXPLAINTHATSTUFF [online]. 2017, Jan 21. Available online at: http://www.explainthatstuff.com/how-speech-synthesis-works.html (Retrieved 16th February, 2017).

- ↑ BLOM, Eric D. Current Status of Voice Restoration Following Total Laryngectomy. Oncology [online]. 2000, Jun 1. Available online at: http://www.cancernetwork.com/head-neck-cancer/current-status-voice-restoration-following-total-laryngectomy (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 LIU, Hanjun, NG, Manwa L. Electrolarynx in voice rehabilitation. Auris Nasus Larynx, 2007, 34.3: 327-332.

- ↑ TARNOWSKA, Czesława. Wspomnienie o profesorze Erwinie Mozolewskim. Pomorski Uniwersytet Medyczny w Szczecinie [online]. Available online at: https://www.pum.edu.pl/__data/assets/file/0009/14868/Wspomnienie_o_profesorze_Erwin_7517.pdf (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ DigiBarn Computer Museum. The Knowledge Navigator concept piece by Apple Computer (1987). DigiBarn Computer Museum [online]. Available online at: http://www.digibarn.com/collections/movies/knowledge-navigator.html (Retrieved 5th January, 2017).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 BROWN, Dale H. et al. Postlaryngectomy Voice Rehabilitation: State of the Art at the Millennium, World Journal of Surgery [online]. 2003, 14 May. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-003-7107-4 Available online at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-003-7107-4 (Retrieved 16th January, 2017).

- ↑ GARDNER, Warren H., HARRIS, Harold E. Aids and Devices for Laryngectomees. Arch Otolaryngol 73(2) [online]. 1961: 145-152. Doi: 10.1001/archotol.1961.00740020151003 Available online at: http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaotolaryngology/article-abstract/1766151 (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 SERRA, A. et al. Post-laryngectomy voice rehabilitation with voice prosthesis: 15 years experience of the ENT Clinic of University of Catania. ACTA otorhinolaryngologica italica [online]. 2015; 35(6): 412-419. Doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-680 Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4755057/ (Retrieved 23rd January, 2017).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 TEN HALLERS, E. J. O. et al. Difficulties in the fixation of prostheses for voice rehabilitation after laryngectomy. Acta Oto-Laryngologica [online]. 2009, Jul 8. Doi: 10.1080/00016480510031506 Available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00016480510031506 (Retrieved 23rd January, 2017).

- ↑ Patrickometry. Alexa is a Revolution for my Disabled Family Member. Amazon [online]. 2015, Sep 6. Available online at: https://www.amazon.com/Amazon-SK705DI-Echo/product-reviews/B00X4WHP5E (Retrieved 21st December, 2016).

- ↑ Alex S. Already very practical for overcoming disability issues. Amazon [online]. 2015, Jun 19. Available online at: https://www.amazon.com/review/RTRDKUJDZCO4B/ref=cm_cr_dp_title?ie=UTF8&ASIN=B00X4WHP5E&channel=detail-glance&nodeID=9818047011&store=amazon-home&tag (Retrieved 21st December, 2016).

- ↑ BOSKER, Blanca. SIRI RISING: The Inside Story Of Siri’s Origins — And Why She Could Overshadow The iPhone. The Huffington Post [online]. 2013, Jan 24. Available online at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/01/22/siri-do-engine-apple-iphone_n_2499165.html (Retrieved 15th December, 2016).

- ↑ KOMNINOS, Andreas. STAMOU, Sofia. HealthPal: An Intelligent Personal Medical Assistant for Supporting the Self-Monitoring of Healthcare in the Ageing Society. Research Gate [online]. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228643857_HealthPal_an_intelligent_personal_medical_assistant_for_supporting_the_self-monitoring_of_healthcare_in_the_ageing_society (Retrieved 6th January, 2017).

- ↑ MIT Technology Review Custom, PwC. AI Drives Better Business Decisions. MIT Technology Review [online]. 2016, Jun 20. Available online at: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/601732/ai-drives-better-business-decisions/ (Retrieved 6th January, 2017).

- ↑ WINARSKY, Norman and MARK, William. The Future Of The Virtual Personal Assistant. TechCrunch [online]. Mar 25, 2012 Available online at: https://techcrunch.com/2012/03/25/the-future-of-the-virtual-personal-assistant/ (Retrieved 16th December, 2016).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 THIBODEAUX, Rose. The Ultimate Guide to Smart Home Compatibility. Home Alarm Report [online]. 2017, Jan 4. Available online at: http://homealarmreport.com/ultimate-guide-smart-home-compatibility/ (Retrieved 11th January, 2017).

- ↑ GOKSEL-CANBEK, N., MUTLU, M. E. On the track of Artificial Intelligence: Learning with Intelligent Personal Assistants. International Journal of Human Sciences, 13(1), 2016, p. 592-601. Doi: 10.14687/ijhs.v13i1.3549 Available online at: https://www.j-humansciences.com/ojs/index.php/IJHS/article/view/3549/1661 (Retrieved 6th January, 2017).

- ↑ MOLDEN, Martin. Employing Apple's Siri to practice pronunciation: A preliminary study on Arabic speakers. TESOL Working Paper Series 13, p. 2-17. Available online at: http://www.hpu.edu/CHSS/English/TESOL/ProfessionalDevelopment/2015_TWP13/02Molden2015Siri.pdf (Retrieved 19th December, 2016).

- ↑ CHINNERY, George M. EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES Going to the MALL: Mobile Assisted Language Learning. Language Learning & Technology [online], 10(1), (2016): 9-16. Available online at: http://archive.is/YU9D. (Retrieved 28th February, 2017).

- ↑ VAN DER TORN, M. A sound-producing voice prosthesis. Amsterdam, 2005. Dissertation thesis. Vrije Universiteit.

- ↑ DART, Tom. Y'all have a Texas accent? Siri (and the world) might be slowly killing it. The Guardian [online]. 2016, Feb 10. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/feb/10/texas-regional-accent-siri-apple-voice-recognition-technology (Retrieved 28th February, 2017).

- ↑ CORBYN, Zoë. Meet Viv: the AI that wants to read your mind and run your life. The Guardian [online]. 2016, Jan 31. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jan/31/viv-artificial-intelligence-wants-to-run-your-life-siri-personal-assistants (Retrieved 10th January, 2017).

- ↑ KENNY, Gavin. I Know Everything About You! The Rise of the Intelligent Personal Assistant. Security Intelligence [online]. 2015, Aug 12. Available online at: https://securityintelligence.com/i-know-everything-about-you-the-rise-of-the-intelligent-personal-assistant/ (Retrieved 9th January, 2017).

- ↑ EGAN, Matt. No one cares about privacy. TechAdvisor [online]. 2014, Mar 24. Available online at: http://www.techadvisor.co.uk/opinion/internet/no-one-cares-about-privacy/ (Retrieved 28th February, 2017).

- ↑ COHEN, P., CHEYER, A., HOROVITZ, E., EL KALIOUBY, R. & WHITTAKER, S. A Future for Personal Assistants. ACM CHI 2016: Panel Session, San Jose, May 7-12, 2016. Available online at: http://www.adam.cheyer.com/papers/chi16.pdf (Retrieved 9th January, 2017).

- ↑ CARROLL, Rory. Goodbye privacy, hello 'Alexa': Amazon Echo, the home robot who hears it all. The Guardian [online]. 2015, Nov 21. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/nov/21/amazon-echo-alexa-home-robot-privacy-cloud (Retrieved 10th January, 2017).

- ↑ WebWhispers.org. Text to speech apps for Phones and Pads. WebWhispers.org [online]. 2017. Available online at: http://www.webwhispers.org/library/TexttoSpeechApps.asp (Retrieved 16th February, 2017).

- ↑ ROMPORTL, Jan. Speech Synthesis and Uncanny Valley. In: Text, Speech, and Dialogue. Cham: Springer, 2014, p. 595-602. Doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10816-2_72 Available online at: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-10816-2_72 (Retrieved 2nd February, 2017).

- ↑ ONES, Rhett. Virtual Assistant Lets You Imprison Your Anime Girlfriend and Feel Loved. Gizmodo [online]. 2016, Dec 17. Available online at: http://gizmodo.com/virtual-assistant-lets-you-imprison-your-anime-girlfrie-1790234598 (Retrieved 22nd December, 2016).

- ↑ BRAZZI, Nicholas. Don't call it "she". It's a computer, not a person. LinkedIn [online]. 2017, Jan 12. Available online at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/dont-call-she-its-computer-person-nicholas-brazzi (Retrieved 13th January, 2017).

- ↑ Advance Health Network. Industry News: Cooper-Rand Electronic Speech Prosthesis. Advance Health Network [online]. Available online at: http://speech-language-pathology-audiology.advanceweb.com/Article/Cooper-Rand-Electronic-Speech-Prosthesis.aspx (Retrieved 13th January, 2017).

- ↑ SHUTE, Brian. There's Nothing Like the Sweet Spot: Placement of the Artificial Larynx. DrShute.com [online]. 1997, Oct. Available online at: http://www.drshute.com/archives/2004/08/theres_nothing.html (Retrieved 16th January, 2017).

- ↑ MOFFET, Bethann, PINDZOLA, Rebekah H. Acustic Properties of Artifical Larynx Speech. ASHA [online]. 1988. Available online at: http://www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/asha/publications/cicsd/1988AcousticProperties.pdf (Retrieved 16th January, 2017).

- ↑ BROOK, Itzhak. The Laryngectomee Guide. American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery [online]. 2015. Available online at: https://www.entnet.org/sites/default/files/LaryngectomeeGuide.pdf (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ MCLELLAN, Charles. How we learned to talk to computers, and how they learned to answer back. TechRepublic [online]. Available online at: http://www.techrepublic.com/article/how-we-learned-to-talk-to-computers/ (Retrieved 3rd March, 2017).

- ↑ The Mad Max Wiki. Charlie. The Mad Max Wiki [online]. Available online at: http://madmax.wikia.com/wiki/Charlie (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ South Park Wiki. Ned Gerblansky. South Park Wiki [online]. Available online at: http://southpark.wikia.com/wiki/Ned_Gerblansky (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ My Name Is Earl Wiki. Electrolarynx Guy. My Name Is Earl Wiki [online]. Available online at: http://mynameisearl.wikia.com/wiki/Electrolarynx_Guy (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ RAWSON, Chris. Siri guest stars on CBS's Big Bang Theory. Engadget [online]. 2012, Jan 30. Available online at: https://www.engadget.com/2012/01/30/siri-guest-stars-on-cbss-big-bang-theory/ (Retrieved 10th January, 2017).

- ↑ WEHNER, Mike. The Simpsons pokes fun at Siri. Engadget [online]. 2013, Nov 4. Available online at: https://www.engadget.com/2013/11/04/the-simpsons-pokes-fun-at-siri/ (Retrieved 10th January, 2017).

- ↑ MEDEIROS, Joao. How Intel Gave Stephen Hawking a Voice. Wired [online]. 2015, Jan 13. Available online at: https://www.wired.com/2015/01/intel-gave-stephen-hawking-voice/ (Retrieved 3rd March, 2017).

- ↑ MCHUGH, Molly. You Can Now Use Stephen Hawking’s Speech Software for Free. Wired [online]. 2015, Aug 18. Available online at: https://www.wired.com/2015/08/stephen-hawking-software-open-source/ (Retrieved 3rd March, 2017).

- ↑ mylexisdhose. Truth singing cowboy. Youtube [online]. 2008, Apr 10. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eshSlxe9qd0 (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ POLDEN, Jake. When smoking does not kill: Smokers receive powerful wake-up call when buying cigarettes from a man with an electrolarynx. Daily Mail [online]. 2015, Sep 2. Available online at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3219431/When-smoking-does-not-kill-Smokers-receive-powerful-wake-call-buying-cigarettes-man-electrolarynx.html#ixzz4W0g49sAC (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ FERNBACK, Jan, PAPACHARISSI, Zizi. Online privacy as legal safeguard: the relationship among consumer, online portal, and privacy policies. New Media & Society, 2007, 9(5), 715–734. DOI: 10.1177/1461444807080336 Available online at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1461444807080336 (Retrieved 2nd March, 2017).

- ↑ MCMILLAN, Robert. IBM Outlaws Siri, Worried She Has Loose Lips. Wired [online]. 2012, May 22. Available online at: https://www.wired.com/2012/05/ibm-bans-siri/ (Retrieved 16th December, 2016).

- ↑ PEMBERTON, Tye. IBM Makes Watson TTS More Expressive. Speech Technology [online]. 2016, Feb 29. Available online at: http://www.speechtechmag.com/Articles/News/Speech-Technology-News-Features/IBM-Makes-Watson-TTS-More-Expressive--109477.aspx (Retrieved 2nd March, 2017).